There are a total of 16 Japanese public holidays. They can range from the typical New Year’s and National Foundation Day, to the more specific Coming of Age Day and the Emperor’s Birthday.

Here you will find a guide to national holidays in Japan: their names, their origin, and fun facts! Let’s go down the list!

New Year’s Day

Ganjitsu 元日, “New Year’s Day”, kicks off Shōgatsu 正月, which is generally the first 3 days of the year. It’s one of the most important Japanese public holidays.

During this time, Japanese people eat a special combination of Osechi-Ryōri (お節料理) consisting of sweet, sour, and dried foods that can keep without refrigeration. This goes back to the days before households had fridges and stores closed for the holidays.

Most Japanese people head to a shrine on New Year’s Day to pray, especially after getting up bright and early to see the first sunrise of the year. People climb mountains for hours in the night to sit and prepare for this sunrise. It’s an activity I highly recommend to anyone visiting Japan during the New Year holidays.

Then there’s the Japanese custom of writing New Year’s Day postcards (年賀状, nengajō) by hand to each and every close family and friend, wishing them a happy new year and letting them know everyone is happy and well (and alive). Children also receive New Year’s gift (お年玉, Otoshidama), money wrapped in envelopes from their parents or grandparents.

Read more about how Japanese people celebrate New Year’s in our article here.

Coming of Age Day

Seijin no Hi (成人の日, “Coming of Age Day”) is on the second Monday of January. It’s a celebration to congratulate those who have reached the age of 20—the age of adulthood in Japan. At local and prefectural offices, young adults gather for speeches in coming of age ceremonies, with women donning long-sleeved kimono (振袖, Furisode) and men in Hakama (袴, men’s formal skirt)—though nowadays men tend to wear a western styled suit. After the formal parts are over, friends group up and have a night out on the town. Oh to be a young adult!

National Foundation Day

On February 11, the country celebrates Kenkoku Kinen no Hi (建国記念の日, “National Foundation Day”). On this supposed day, Emperor Jimmu came to the throne on the first day of the first month of what was the lunar calendar at the time. It’s a reflection on Japanese citizenship and pride.

Vernal Equinox Day

Usually somewhere between March 19-22 based on astronomical measurements, Shunbun no Hi (春分の日, “Vernal Equinox Day”) started out as a Shintoist related event. It now celebrates the spring equinox, when daylight and night hours are the same. It’s the official change of the seasons, just as the Shuubun no Hi (秋分の日, “Autumnal Equinox Day”) stands for the changing into Autumn.

The Vernal Equinox is usually a time to visit loved ones’ graves, pay homage to ancestors, and renew their lives by cleaning their homes. People take the day off work to spend time with their families and take in the coming of the spring season after a tough winter.

Showa Day

Held on April 29, Shouwa no Hi (昭和の日, “Showa Day”) is a holiday in honor of the birthday of Emperor Shouwa Hirohito, reigning emperor from 1926 to 1989. The meaning of this holiday is to reflect on the turbulent 63 years of the Shouwa era, a time consisting of Japanese invasions of foreign countries, attempted coup d’états, totalitarianism, World War II, and the rocket rise of the Japanese post-war economic miracle.

It also kicks off the all important Golden Week (ゴールデンウイーク), the busiest time of the year for travel in Japan. This week is the mother of all Japanese public holidays. Showa Day, Constitution Memorial Day, Greenery Day, and Children’s Day—depending on the year—can all line up to form an ultimate holiday week (or more!) for busy Japanese salarymen, and some companies even close down completely. It’s busy, it’s an expensive time to fly, but it’s warm and it’s fun!

Constitution Memorial Day

Kenpou Kinenbi (憲法記念日, “Constitution Memorial Day”), on May 3, celebrates the creation of the 1947 new constitution of post-World War II Japan.

Greenery Day

Midori no Hi (緑の日, “Greenery Day”) is officially a day to commune with nature. It was meant to acknowledge Emperor Shouwa’s admiration for plants without mentioning his name in the holiday, as the wartime emperor can be controversial. In practice though, it’s another day that forms the ever-loved Golden Week.

Children’s Day

Kodomo no Hi (子供の日, “Children’s Day”) wraps up Golden Week, taking place on May 5. Meant to celebrate children as well as their fathers and mothers, on this day you’ll find carp fish-shaped flags hung on poles over their homes. A black carp above represents the father, red for the mother, and additional carps below for the children. Carps are part of a Chinese legend about a carp swimming upstream to become a dragon and thus flying up to heaven.

Marine Day

Held on the third Monday of July, Marine Day (海の日, Umi no Hi) is a celebration of the ocean and its bounty. As an island nation, the ocean always has and always will be a very important part of Japanese culture. It also usually comes around the end of the rainy season, which makes it even more a reason for people to get out and take advantage of the summer sun by having a day on the beach. When I lived on Tanegashima, the day would often bring out kids and adults alike for a big beach cleanup day.

Mountain Day

Just like Marine Day, Mountain Day (山の日, Yama no Hi ) is a Japanese public holiday to be with the mountains and appreciate the blessings it brings. Since 2016, every August 11 has been Mountain Day. Along with its endless coastlines and connection to the ocean, Japan’s rugged mountains deserve just as much admiration and respect.

Respect for the Aged Day

Keirō no Hi (敬老の日, “Respect for the Aged Day”) is on the third Monday of September because of the Happy Monday System. This system moved a number of Japanese public holidays to Mondays in order to allow for more three day weekends for those who work a five-day week. In honour of elderly citizens, Respect for the Aged Day is a nice glimpse into how the Japanese respect their elders.

Health-Sports Day

Held annually on the second Monday of October, Taiiku no Hi (体育の日, “Health-Sports Day”) is in commemoration of the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo. The government encourages sports and an active lifestyle.

Japanese schools hold their annual Undoukai (運動会) on this day, an enormous event for every school in which students participate in physical events, ranging from track-and-field, to tug-of-war and local regional games. Teachers challenge students in relays, parents join goofy races carrying their kids or juggling sports equipment, and the entire day turns into an outdoor festival. It’s quite an event to see!

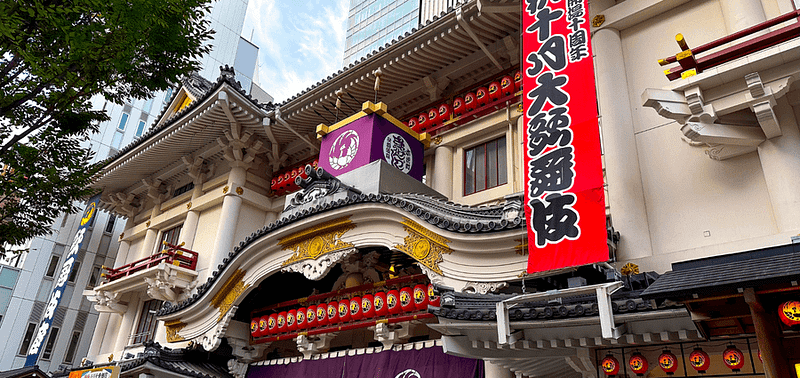

Culture Day

Culture Day (文化の日, Bunka no Hi ) is held every November 3 to promote culture and academics. Art exhibitions are held and awards given to artists and scholars.

Labor Thanksgiving Day

Kinrou Kansha no Hi (勤労感謝の日, “Labor Thanksgiving Day”) is on November 23, as a day for giving thanks to one another for hard work and productivity. Its roots come from an ancient harvest festival, where the Emperor would dedicate the year’s harvest to the gods.

The Emperor’s Birthday

The current Tennō Tanjōbi (天皇誕生日) is on February 23.

This is one of two occasions that the public may enter the inner grounds of the Imperial Palace. On this day, the Emperor and Empress, as well as members of the imperial family, wave hello to the congratulatory crowds from the palace balcony. What a way to celebrate a birthday, huh?

Punny holidays

On top of its real holidays, Japan has pun-filled “holidays” that take advantage of the way the language works: a non-phonetic writing style containing multiple pronunciations of the same character, due to its roots in Chinese characters intertwined with its own native pronunciations. In other words, it means tons of room for knee-slapping, groan inducing puns.

Though nobody gets a day off for these days, they can come with bonuses!

Every month on the 29, for example, is Niku no Hi (肉の日, “Meat day”). Why, you ask? In Japanese, the number two is pronounced “ni,” and the number nine “kyuu” or “ku.” Put that together and you get ni-ku, or the word for meat. Get it? Ha! Browse the supermarkets on this day and you’ll often find meat on sale for great prices!

On 11/22 couples can sometimes find special deals due to 11 looking like “ii” meaning “good,” and 22 pronounced as “fufu,” meaning couple. The puns are endless, and some are quite a stretch, but it’s a fun way to see how the language works.

And that’s it for our guide to Japanese public holidays! It may seem like there are quite a lot of national holidays, but for as hard as they work, every single one is well deserved. Perhaps even more are needed! Come over and enjoy a holiday or two of your own in Japan, but keep a look out for Golden Week. If you’re wondering why ticket prices are so expensive, this could be the reason!

Contact us today to know the best way to enjoy life in Japan for you!

If you like to read more about Japanese culture, make sure to follow our blog where we cover everything you need to know about Japan!