Shintō and Buddhism are Japan’s two major religions, with Shintō recorded as far back as the 8th century, although its existence has probably been much longer. Buddhism was brought from China in the 6th century, and both religions have co-existed harmoniously in Japanese culture since.

Although many Japanese may identify as a Buddhist, Shintoist or both, religion typically does not play a large role in the everyday life. However, many cultural rituals and ceremonies are religious, based on one or the other, like births, weddings, funerals, New Year’s and seasonal festivals, also known as matsuri.

Let’s learn the meaning and basic steps of worship at a Shintō Shrine in Japan. Please note that these guidelines are very by-the-book, and are not as closely followed nowadays.

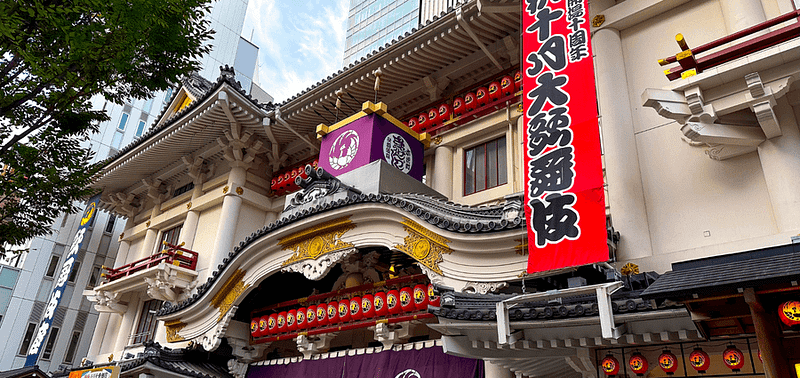

Jinja

Shintō shrines, called jinja (神社), are places of worship and the dwellings of the Shintō gods, called kami (神). It also keeps sacred objects within for safekeeping, that are not seen by the public.

Japanese people may visit jinja during New Year, setsubun (節分), shichigosan (七五三), and other festivals. Newborn babies are traditionally brought to the shrine soon after birth, and Japanese traditional weddings are held at jinja.

Sanpai

Be mindful that jinja is a place of worship, as such, you should be dressed appropriately and be respectful of customs. Especially when entering a shaden (社殿), or somewhere special within the jinja, men should wear suits with ties and women with suits or dresses. The act of worship is called sanpai (参拝).

How to sanpai

-

- Bow once before walking through the torii. Be mindful that you are entering a place of worship.

- Purify yourself with the water at the chozuya (手水舎), or sometimes called chozusha/temizuya/temizusha. Scoop water with the hishaku (柄杓) in

your right hand and pour over your left. Switch sides and pour on your right hand with your left. Hold it in your right hand again, pour water in the palm of your left hand to carry to your mouth to rinse. Purify your left hand again with your right, then straighten the hishaku to let the water down on the handle, then place back, facing down.

- Walk on the side of the sandō 参道 (a road approaching a shrine) toward the altar.

- Bow before the saisenbako (賽銭箱) and throw lightly your offering into the box. You can put in any amount but it is said that 10-yen coins and 500-yen coins are unlucky. On the other hand, 5-yen coins are said to be lucky to bring in good fate, because goen (五円), or 5 yen, sounds like goen (ご縁), or fate. If using paper bills, they should be new bills placed in a white envelope with your name and address on it, prior to offering.

- Pull the rope to ring the bell to expel the demons. If it’s crowded, you can skip this step.

- Bow twice, clap twice, pray and bow once. Called nirei-nihakushu-ichirei (二礼二拍手一礼), you should bow deeply twice, then place the palms of your hands together before your chest in a prayer position, separate them to around shoulder-width and clap twice, then keeping your hands in front of your chest in prayer position pray quietly, then lower your hands to your sides and bow once again deeply.

- Proceed back down the stairs. You can perhaps purchase an omikuji (おみくじ), omamori (お守り), hang an ema (絵馬), or walk around the rest of the property.

Torii

The torii (鳥居) is a red gate separating the rest of society from the dwelling of the gods. Bow before entering, or walking through it, as you would when entering someone’s house. Bow again once you are finished visiting, after going through the torii, facing it again.

How to walk on sandō

The middle of the sandō, or walkway, is reserved for the passing of the gods. Therefore, you should avoid walking in the middle, to be respectful to the gods. When you need to cross the middle of the sandō, lower your head to show respect, or bow once toward the altar before crossing.

Omikuji

Omikuji are fortune-telling paper strips that can be purchased for around 100 or 200 yen, depending on the Shintō Shrine. Some come in the form of vending machines, and others use a pillar box with long, thin sticks that are shaken and one stick chosen. Generally, the paper will show your overall fortune in ranking of daikichi (大吉), kichi (吉), chukichi (中吉), shokichi (小吉), and kyo (凶), meaning excellent luck, good luck, middle luck, small luck, and bad luck respectively.

Each shrine has different beliefs, but generally people take home their omikuji so that they can keep the luck with them. If you draw back luck, however, many people will tie it to a designated place within the grounds of the shrine.

Omamori

Omamori are amulets sold at shrines and temples in Japan, and mean “to protect.” There are so many different varieties of design for different functions, such as for traffic safety, better fortune, passing examinations, prosperity in business, finding a soulmate, healthy pregnancy, etc.

They are purchased at the beginning of the year and are to be kept with you throughout the year, then burned, not disposed.

Ema

Ema are a small wooden prayer plaques, literally “picture-horse.” Shintō worshippers write their prayers or wishes on them, then they are hung at the shrine, where the gods are believed to receive them.

Now that you know about the different elements of a Shintō Shrine you’ll have a whole new experience next time you visit. And for those of you who are already in Japan and worried about passing the JLPT, how about visiting a shrine in the near future? Every little bit counts!

For more information about Japanese culture keep following our Go! Go! Nihon blog.